Utah Lepidopterists' Society

Founded 6 Nov 1976

|

|

Utah Lepidopterists' Society Founded 6 Nov 1976 |

|

| History | Mission | Meetings | Bulletin | Checklists | Links | Community | Field Trips | Habitat | Members | Kids | Contact Us |

|

|

|

|

|

Previous lepidoptera publications describing the Papilio indra complex

have labeled it as rare, fragile, isolated, and so forth. For example, William

H. Howe describes it as follows: "The Papilio indra

complex shows a considerable degree of geographic variation, especially in the

southern parts of its range. Throughout its range the species is generally

uncommon and specimens are rare in collections."

Clifford D. Ferris and F. Martin Brown add, "Because of its isolated

habitats, indra is poorly represented in collections."

Furthermore, according to John Adams Comstock, speaking of P. indra

indra in Calif, "is one of our rare species, occurring in

the higher altitudes of the Sierras...It is a difficult butterfly to capture,

being rapid and erratic in flight." (Italics added.) But today,

because of work by researchers and by many collectors who have become

impassioned with indra, we know that it is not only more common than

previously perceived--it has been recorded in every county in Utah save four;

Sanpete, Iron, Wasatch, and Piute--but also, it is well represented in some

collections.

The Papilio indra complex in Utah flies in a variety of habitats from

desert swells, reefs, and limestone hills to the tops of the Wasatch Mountains.

In fact, the butterfly has even been seen crossing valley floors between

mountain ranges! It is true that indra does fly in some hostile

environments. Its population numbers have been known to fluctuate drastically

from year to year depending upon climate and parasitism. A large colony of P.

indra minori in Emery County, was all but depleted between 1993 and 1995

due to heavy parasitism. Fortunately, this year (1996), minori has made

a recovery there. One of the population stabilizing mechanisms of indra

is the fact that their pupae can prolong diapause for several years in order to

insulate against harsh or unfavorable conditions.

One of the elements that gives indra such an appeal to some collectors

is its beauty coupled with its geographic variation. The indra swallowtail's

geographic variation is peculiar in the effect that colonies which fly in moist

montane habitat such as P. indra indra show much less individual

variation than do colonies from the desert or from a semi-arid origin such as P.

indra nevadensis or P. indra minori. The same phenomenon also

seems to occur in California as montane colonies of pergamus and indra

indra show a lower degree of individual variability as compared to the

desert races of fordi and martini.

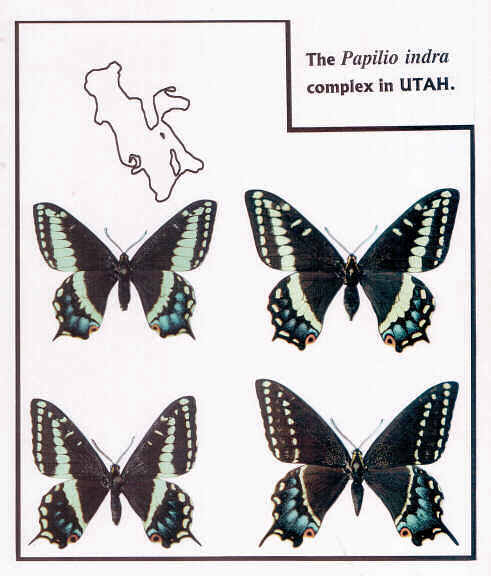

Utah currently has four varieties of indra; three named subspecies

which include the typical race, minori, nevadensis, and one

unnamed variety, "bonnevillei." Unlike its cousins from the machaon

group, Papilio indra adults are not sexually dimorphic. In many Utah

habitats, excepting most colonies of P. indra minori and P. indra

nevadensis, indra flies sympatric with Papilio zelicaon;

the former usually flying 7 to 10 days after the latter. The two species also

share many of the same larval foodplants. However, zelicaon generally

has a broader base of foodplants as compared to indra.

Although difficult and time-consuming, many collectors have been able to obtain

attractive series of the different varieties of indra through rearing

its caterpillars. One of the difficulties of rearing indra in the lab

is the few species of plants--usually in the Lomatium and Cymopterus

genera--which the caterpillars will accept. Obtaining these specific plants many

times requires long distance travel to obtain. Another problem with raising indra

in the lab that can be overcome through practices later discussed in this

publication is their high susceptibility to microbial death. The two most common

varieties of microbes that kill indra immatures are viruses and

bacteria.

Others have obtained a decent series of some races of P. indra by

collecting adults on the wing. Although Comstock describes the butterfly as

being difficult to capture and erratic in flight, a little patience can overcome

this obstacle through observation. In other words, indra males

oftentimes will repeat their "erratic" courses as they fly similar

aerial routes and land generally in the same spots. By predicting this

repetitious behavior, specimens can be netted more easily. Some higher altitude

males of P. indra indra exhibit this repetitive flying behavior, and

have even been known pause from their aerial stunts in order to land and bask on

snow banks!

Females, on the other hand, are much easier to capture as they more casually

flitter in the vicinity of their larval hostplants. (The only exception to this

is females of P. indra minori which tend to traverse their habitat in

search of larval hostplant with much more haste.)

PART I: THE FOUR UTAH VARIETIES OF PAPILIO INDRA

Papilio indra indra

General:

The Type Locality of P. indra indra is vicinity of Empire, Clear Creek

County, Colorado; Reakirt 1866. It is the shortest tailed race; some individuals

exhibiting nothing more than a "stub." The nominate race is univoltine.

The flight period in Utah varies depending upon elevation, snowfall, and larval

hostplant. In the Bear River Mountains and in other isolated locations along the

Wasatch Front where indra indra utilizes Lomatium grayi var. grayi

between the elevations of 5000' to 7000', indra flies from mid-May to

late July.

On the other hand, higher up in the Wasatch Mountains, where the larval

hostplant (L. kingii) grows at around 8000' to 10,000', the flight

period varies from around mid June to early September.

Utah Distribution and Habitat:

As discussed previously, the montane habitat of P. indra indra includes

the Wasatch, Oquirrh, Stansbury, Bear River, and Uinta Mountain Ranges. Higher

altitude males patrol and perch all day in search of females. Some of these

males have been known to descend several thousand feet to canyon floors to

nectar near rivers. (I.e, Provo Canyon, Utah County, and Big Cottonwood and

Millcreek Canyons, Salt Lake County.)

Bionomics:

As stated earlier, the principal larval foodplant for P. indra indra in

the Wasatch Mountains is Lomatium kingii (narrowleaf lomatium,) and the

larval foodplant in the Bear River Mountains is Lomatium grayi var. grayi (milfoil

lomatium.)

The ova is yellow-green, and is laid principally on healthy plants' peripheral

ventral stalks. After a day or so, the ova develops rings and then turns black

before hatching. From the time an egg is laid to the time it hatches is roughly

six days in nature and five days in the lab. (Assuming room temperature.)

The young first instar larva is black with a thin, white saddle. As the larva

moults into later instars, small white and yellow-orange speckles appear. Larvae

of P. indra are much more timid than those of P. zelicaon.

The mature larva varies from black with off-white stripes to nearly all black

with small yellow-orange dots. Hibernation is as pupa. For some reason, most

lab-reared pupae emerge after two years of winter. Some pupae have been known to

diapause for up to seven years.

Papilio indra minori

General:

The Type Locality of P. indra minori is Black Ridge Breaks, Mesa

County, Colorado; Cross 1936. Minori is one of the most beautiful races

of P. indra. Its large size with long tails combined with thin to

intermittent cream bands and generous blue dorsal hindwing scales are

diagnostic. Adults display a significant amount of individual variation. The

bands on some individuals of minori are completely obsolete; showing

the phenotype of what essentially is a black and blue swallowtail. It is the

opinion of the author that this form kaibabensis which most authorities

treat as a distinct subspecies really is a genetic drift morph of minori for

two reasons. First, the kaibabensis form appears at least seldomly in

mostly all minori populations. Again, its just an example of individual

variation. Second, the habitat and bionomics of the two taxa are virtually

indistinguishable.

Males hilltop on the tops of reefs, buttes, or even sheer peaks in search of

females. In fact, minori males have shown intense aerial battles

against one another in competition for females. Females, on the other hand,

oftentimes fly in lower portions of buttes, or even in desert floors or swells

in search of its larval hostplant. (Females only hilltop once to mate.) It is

multivoltine depending upon rainfall; with up to three broods per year.

Utah Distribution and Habitat:

The distribution of minori in Utah is considerable. According to W.H.

Whaley, over 50 distinct colonies can be found over Central to

South-Southeastern Utah badlands. This distribution includes, but is not limited

to, the West Tavaputs Plateau, Cedar Mountain, San Rafael Swell, San Rafael

Reef, Capitol Reef National Monument, Henry Mountains, Cockscomb Ridge, La Sal

Mountains, Abajo Mountains, and Monument Valley south to Northern Arizona.

Bionomics:

The larval hostplants of minori differ depending upon venue. In the San

Rafael Swell, Cedar Mountain, San Rafael Reef, Capitol Reef National Monument

areas, larvae utilize Lomatium junceum (rush lomatium.) At the

Cockscomb Ridge, Monument Valley, and Abajo Mts, larvae use Lomatium parryi (parry

desert parsley.) Also at Monument Valley and areas adjacent to Moab, larvae use Cymopterus

terebinthinus (rock springparsley.) All of these larval hostplants are

unique because they, for the most part depending upon rainfall, stay green and

healthy from spring until fall; which accounts for the butterfly's ability to

have multiple generations in one year.

Photos: Lomatium junceum & Lomatium

junceum (closeup with ova)

The ova is yellow-green; developing rings and then turning black before

hatching. The young larva is black with a white saddle. It is interesting to

note that young minori larvae have a broader white saddle than young indra

indra larvae have. The large mature larva is gorgeously arrayed with bright

pink and black stripes strewn with orange dots. Immatures, unfortunately, are

heavily subjected to several varieties of parasites. Egg parasites have recently

been discovered in addition to the ever-so-prevalent small wasp parasites that

kill third instar larvae and maggot parasites that kill fifth instar larvae.

Hibernation is as pupa.

Papilio indra nevadensis

General:

The Type Locality of P. indra nevadensis is Jett Canyon, Nye County,

Nevada; Emmel and Emmel 1971. In Utah, P. indra nevadensis is also

known as P. indra nr. nevadensis. It is a long tailed race of indra.

Amongst all the varieties of indra in Utah, nevadensis shows

the most drastic example of individual variation with specimens looking like fordi,

martini, panamintensis, and even pergamus. Nevadensis for

the most part is univoltine with less than 1 percent of lab-reared pupae

emerging during the same year. Adults of the Nevada Swallowtail fly early in the

year; from mid to late March to early May.

Utah Distribution and Habitat:

The distribution of nevadensis in Utah is restricted to Washington

County.

Bionomics:

Nevadensis immatures utilize two species of Lomatium in

Washington County. In the vicinity of St. George, Lomatium scabrum

(cliff lomatium) is the larval hostplant. Leaflets of L. scabrum burn

off by mid to late May; which accounts for its one brood. However, leaflets of Lomatium

parryi, which is its foodplant, further north, do not burn off until the

fall. As such, it is plausible that nevadensis could at least have a

partial second brood. Admittedly, more research needs to be done in this area.

Under typical conditions, females will only lay on healthier L. scabrum plants

located between rocks or at the base of desert washes because these plants will

thrive long enough to support the larva to maturity. However, in certain years,

when population numbers are extremely high, it is interesting to note that

females sometimes will oviposit on plants that cannot support the larva to

maturity. Some Navajo Sandstone hills in Washington County do not have Lomatium

scabrum on them except for North-facing washes and slopes. These hostplants

only exist and survive there for two reasons: First, these washes and slopes

accumulate more moisture and can support the roots of these plants. Second,

plants in this area receive less direct desert sunlight as compared to south,

east and west facing slopes.

The mature larva is similar to P. indra minori and is striped with

bright pink-peach and black bands with yellow-orange spots. The pupa is salmon

in color and camouflages well against Navajo Sandstone. As is true with all

subspecies of indra, hibernation is as pupa.

Papilio indra "bonnevillei"

General:

Currently, "bonnevillei" is an unnamed race of Papilio indra.

The name was originally under consideration by C.F. Gillette in 1987 and later

dropped. Currently this unnamed race, also regarded as "West Desert indra"

by local collectors, is being researched and considered to be named as a

subspecies by W.H. Whaley.

The presenter of this publication feels that "bonnevillei" should have

subspecific recognition for several reasons: First, "bonnevillei" is

geographically isolated from nevadensis or nr. nevadensis.

Second, P. indra nevadensis never have short-tailed morphs; P.

indra "bonnevillei" does. Third, over a long series, "bonnevillei"

has consistently more blue in the dorsal hindwings as compared to nevadensis.

Fourth, some "bonnevillei" females exhibit extremely wide dorsal

forewing bands that rival even P. indra fordi let alone nevadensis.

Fifth, nevadensis documented larval hostplant Lomatium scabrum

grows where "bonnevillei" flies. However, to date, "bonnevillei"

immatures have not been found on it. Sixth, mature larvae of "bonnevillei"

are drastically different to Washington County nevadensis.

"Bonnevillei" is short to medium tailed, and has one flight per year.

The flight varies depending upon winter precipitation. At 5000', "bonnevillei"

generally flies from mid/late April to mid/late May.

Utah Distribution and Habitat:

Colonies of "bonnevillei" exist in many North-South ranges in Utah's

West Desert including but not limited to the Dugway Range, Thomas Range, Fish

Springs Range, House Range, Confusion Range, Little Drum Mountains, and Wah Wah

Mountains. All of these mountain ranges contain Limestone and exist in the

vicinity of what was Lake Bonneville. These limestone hills is where the larval

hostplant lives.

Bionomics:

The larval hostplant is Lomatium grayi var. depauperatum. This plant

seems to die off faster than any other host of indra. The young larva

has perhaps one of the most slender white saddles as compared to other

subspecies of indra. As the larva matures, this saddle has been known

to disappear altogether. Third instar larvae of "bonnevillei" change

their resting position to the base of the hostplant where they are difficult to

find. The mature larva has two basic forms from mostly black with tiny yellow

dots to black with medium cream bands. The mature larva somewhat resembles the

larva of P. indra indra.

Utah Papilio indra Subspecies and Larval Foodplant Matrix

|

Food Plant |

P. indra indra |

P. indra minori |

P. indra nevadensis |

P. indra "bonnevillei" |

|

Lomatium grayi var. grayi |

dLF |

NO |

NO |

YES |

|

Lomatium grayi v. depauperatum |

YES |

NO |

NO |

dLF |

|

Lomatium junceum |

YES |

dLF |

YES |

YES |

|

Lomatium kingii |

dLF |

YES! |

YES! |

YES! |

|

Lomatium parryi |

??? |

dLF |

dLF |

??? |

|

Lomatium scabrum |

??? |

??? |

dLF |

NO |

|

Cym. terebinthinus |

YES |

dLF |

dLF |

YES |

**All subspecies of P. indra will gladly

and readily accept L. kingii.

dLF = = Documented Larval Foodplant

YES = = Suitable Lab Foodplant

NO = = Not Suitable Lab Foodplant

??? = = Unknown

(B) P. i. "bonnevilli" 5th instar on L. grayi

(C) P. i. minori 4th instar on C. terebinthinus

(D) P. i. minori 5th instar on L. junceum

References

1. Emmel, Thomas C. and Emmel, John F. 1973. The Butterflies of

Southern California p. 12.

2. Howe, William H. 1975. The Butterflies of North America p. 396.

3. Ferris, Clifford D. and Brown, F. Martin 1981. Butterflies of the Rocky

Mountain States p. 184

4. Comstock, John Adams. 1927. The Butterflies of California, p. 21

5. Gillette, C.F. Col. Utahensis: Journal of the Utah Lepidopterists' Society

l984 4.2, p.34.

6. Whaley, W.H. Personal Communication. 17 Jul 1996.

7. Gillette, C.F. Col. Personal Communication. 5 Jul 1996.

8. Whaley, W.H. ibid.